- Microbiomes are important in improving the prevention and treatment of cancer and chronic viral infections.

Christian Brechot, MD, PhD

In the previous editions of our blog, we have emphasized the need to consider the microbiomes, not only humans but also animals, soils, and oceans, when discussing how our lives are being affected by our nutrition and our environment.

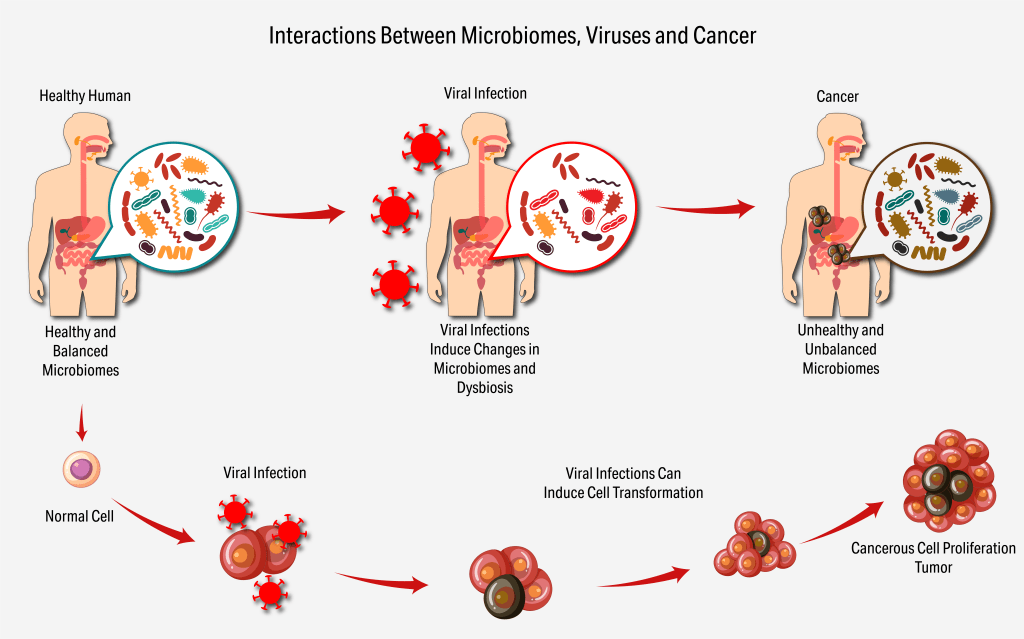

A new paradigm has emerged that might profoundly transform our approach to cancer and some chronic viral infections.

Indeed, microbiomes impact the outcome of infections by viruses and the response to anti-cancer therapies and their side effects! And this opens new avenues for improving the prevention and treatment of cancer and some dangerous chronic viral infections.

There is ample evidence that the gut microbiome shows unique microbial compositions among various cancers; also, it is clear that each tumor and its metastases exhibit an intrinsic microbiome that significantly impacts the tumor micro-environment and the overall progression of the cancer. Importantly, there is now evidence for the impact of such gut and tumor microbiomes on the response to immunotherapy and chemotherapy; as examples, transplantation of the intestinal microbiota from a patient who has responded to immunotherapy to a previously non responder patient can significantly improve his response to further therapy; this has been in particular shown for melanoma and lung cancer.

Treatment with immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) has markedly improved the survival of several cancers. However, a significant proportion of patients show primary or acquired resistance to treatment (up to 50% of patients with melanoma, and 25–44% of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer). In this context, the composition of the gut microbiome appears to be both predictive and prognostic of therapeutic response to ICB. These findings have led to microbiome-based treatment strategies to enhance clinical response to ICB and to mitigate their toxicity. Of note, some prebiotics-based strategies have been shown to improve the efficacy of some anticancer treatments. Regarding the intra-tumoral microbiome, advances in next-generation sequencing (NGS)techniques offer a more precise evaluation of the composition and function of the microbiome and its impact on the microenvironment. Yet, it is still unclear why certain intratumor bacteria promote tumorigenesis, while others trigger antitumor immune responses.

Moreover, there is now clear evidence that gut microbiome dysbiosis is an important factor driving the long-term complications of viral infections, such as, for example, HIV and HPV.

HIV

Many people living with HIV (PWH) are now achieving a life expectancy approaching that of the general population. This is related to the progress of effective antiretroviral therapies (ART). Yet, unfortunately, such patients frequently show accelerated aging with increased risk of age-related non-communicable diseases (NCD). Inflammation is the main driver of such complications and is, at least in part, related to gut dysbiosis. Indeed, HIV infection induces both disruption of gut-associated lymphoid tissue, microbial translocation, and an overall shift in gut microbiome composition, resulting in gut dysbiosis. HIV chronic infection is associated with the development of cancer. AIDS-defining cancers (ADCs: Kaposi’s sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma [NHL], invasive cervical cancer) are traditionally distinguished in HIV-infected patients; other cancers are referred to as non-AIDS-defining cancers (NADCs). NADCs, in turn, are usually classified into virus-related cancers (HPV-, EBV-, and HCV-related cancers) and virus-unrelated cancers

10–20% of all deaths of HIV positive individuals are attributable to cancer, and nowadays, people living with HIV still have a 1.6–1.7-fold greater overall risk of cancer development relative to the general population, and the risk is rising with age. This can be explained by the association of chronic inflammation, immunosuppression, and the frequent coinfection with other oncogenic viruses (Epstein-Barr Virus [EBV], Human Herpesvirus 8 [HHV-8], Human Papillomavirus [HPV], Hepatitis B and C Viruses [HBV, HCV).

Thus, understanding how gut dysbiosis, inflammation, and cancer development are connected is crucial for improving the health outcomes of PWH and identifying those at higher risk.

HPV

Nearly 90% of women are exposed to HPV; most infections resolve; however, about 10% persist, and this persistence is associated with increased risk of cervical cancer. Indeed, High-risk types like HPV 16 and 18 are the leading cause of cervical cancer. Importantly, HPV 16 and, to a lesser extent, 18 are associated with other cancers in men and women, such as head and neck (mostly oropharyngeal), anal and penis cancers

Several studies have now demonstrated that HPV infection is associated to dysbiosis of the vaginal and cervix, characterized by a low proportion of Lactobacillus and increased anaerobic bacteria. A dysbiotic cervicovaginal microbiome is more permissive to persistent HPV infection; it increases viral oncogene expression and integration of its genome, key steps in cervical carcinogenesis, and this eventually leads to cervical dysplasia and cancer. Dysbiosis fosters a pro-inflammatory environment, and chronic inflammation further exacerbates epithelial damage, thus favoring oncogenesis. Finally, dysbiosis also impairs mucosal barrier function, stimulating local inflammation and further promoting viral persistence and genome integration.

Of note, the Microbiota of Hispanic women also frequently exhibits a low lactobacillus distribution, thus resembling that of HPV-infected women, and this likely increases their susceptibility to persistent infections. These findings highlight ethnic variability in microbiota composition and its influence on HPV persistence and cancer progression.

Thus, connecting the fields of microbes and cancers (Microbial Oncogenesis) is a major emerging field with a huge potential for innovation and a target for large-scale funding.

In this context, the University of South Florida (USF) Microbiomes Institute, the USF Virology Institute, and the Tampa General Hospital (TGH) Cancer Institute are launching a consortium which will merge these three highly renowned research and clinical Institutes, it will investigate how the interactions between some cancer-associated viruses and the huge populations of bacteria (named as “microbiomes”) present in the gut and the cancer tissues can favor persistence of chronic viral infections and growth of cancer and its resistance to treatment. The consortium will merge the efforts of the best experts in these different fields of medicine and should offer a transformational approach to cancer treatment and prevention strategies.

- Local Food Systems: Underestimated but Critical Public Health Tools

Organic local farmers and public health professionals share a lack of appreciation and recognition for their impact on a community’s health. Indeed, promoting healthier diets and practices and growing healthy food are perceived as unglamorous. However, their effects are physically, mentally, and financially less painful than surgery, hospitalization, and recovery. Local Food System stakeholders and public health professionals deserve recognition for the real but invisible value they add to their communities. In fact, several school gardens or an acre farm will provide years of health education to hundreds of individuals at a fraction of the cost of a single major surgery.

How could a Local Food System be a public health tool?

Unlike the global food system, local Food Systems (LFS) produce food near where it is consumed. In the current global system, food travels an average of 1500 miles through an efficient but fragile, rigid, and complex distribution network, sadly illustrated during the recent COVID pandemic and conflicts.

While it is unlikely that LFS will replace the global food system soon, LFS have growing roles: they add community resilience, provide multiple tangible and intangible dividends, and significantly impact a community’s quality of life. Rome and Havana are two extreme examples, according to RUAF, an international urban farming research institute based in the Netherlands. Growing 200 acres of broccoli, a California farmer dependent on the global food system is inevitably disconnected from his harvest consumers by distance, harvest volume, and the many distribution intermediaries. In contrast, by growing a few rows of broccoli, among many other crops, many local farmers will likely have direct contact and a relationship with those eating their harvests.

Ripe broccoli cabbage growing in garden ready to harvest Economic impact

LFS’s economic impact is substantial and more significant than manufacturing. Local labor is its main expense; few and minimal purchases of seeds and supplies are made outside the immediate community. LFS creates good direct and indirect local jobs in a new ecosystem, favoring an entrepreneurial mindset and recirculating revenues with a high economic multiplier impact.

Health and social impacts

Small local farms offer a wide variety of products whose freshness improves quality and nutrient density, enabling healthier diets and potentially reducing chronic diseases. Urban farms, homes, and community gardens foster physical activity and a therapeutic connection to nature and allow children an early acquisition of healthy microbiomes with lifelong immune system effects. Sharing the concept that “We are what we eat ATE” illustrates vividly that health is a personal, important choice and that “Healthy food is not grown on sick soil.” Therefore, know where it was grown and who grew it.

Community gardens promote local sustainability and food security.

Socially, gardens and farms serve as a “third space,” a neutral ground that encourages grounding and social interaction. It’s a space where food and nature bring people together, fostering a sense of community and reducing social disparities. In this context, socioeconomic status, race, and other inequalities are set aside in favor of shared interests and enriching exchanges. In London, for example, through the National Health System, elderly residents who are often isolated are paired for garden activities with mentally challenged individuals. In Belgium, some retirement homes share a garden with a school to promote intergenerational exchanges. Those human interactions benefit both groups. Food and gardening are strong cultural and identity elements, creating valuable senses of place and purpose.Educational impact

Farms, as well as community, home, and school gardens, are engaging outdoor science classrooms, encouraging experiential learning, teaching resilience, nurturing, and success by growing vegetables and flowers to share with family and neighbors. Adults reconnect with nature, discover where their food comes from, and expand their taste buds’ horizons by exploring new vegetable varieties, generating demand for freshness and a broader range of products from local farmers. Farms and gardens are an antidote and a counterpoint to the excesses of technology dependence.

Environmental impact

An LFS is a short food distribution circuit that reduces food miles and food and yard waste by creating a demand for compost. More green space and organic farming promote soil and water conservation, increase biodiversity and microorganism density, and minimize pesticide, herbicide, and fungicide residues on food. Farms and gardens offset heat islands in urban areas, store water, and reduce runoff.

In conclusion

Local Food Systems are a high-impact, low-hanging fruit in the quest for better public health and a healthier environment. They create stable jobs, improve public health through improved diets, and contribute to the mental health of more resilient and engaged residents. At the heart of this system is a growing collaboration between local farmers and public health professionals, working in the shadows to improve their community’s quality of life.

Continuous quality-of-life improvements depend primarily on recognizing the societal value of farmers and public health by fostering greater public awareness of their contributions, anchored on healthy soil as a basis for healthy plants and, therefore, healthy humans. - The microbiomes revolution

The microbiomes revolution:

Medicine of humans, medicine of the soils and oceans.

Understanding microbiomes to preserve soil oceans and human health in a shared destiny.

The Impact

The impact of the human microbiome on human health has now been increasingly recognized. However, the connections and interactions between human, soil and oceans microbiomes are still underappreciated.

Ancient Dominance: Bacteria’s 4.2-Billion-Year Reign Far Outlasts Humanity

Microorganisms and bacteria in particular, have occupied the earth for approximately 4.2 billion years, multicellular organisms for approximately 600 million years and humans a mere two hundred thousand years a miniscule fraction of bacteria lifetime on earth.

Evolution of life with round timeline for living creatures development outline diagram. Origin of earth and further years process with bacteria, algae, mammals and humans creation vector illustration. Bacteria Reign: Earth’s 70-Gigaton Microbial Giants Dwarf Humanity’s Biomass

Today bacteria alone represent an estimated biomass of 70 gigatons or 1200 times the 0.06 gigatons representing the weight of eight and a half billion humans. This disproportion illustrates the key role of bacteria in the natural world from two and half mile below the surface of the earth to the upper reaches of the atmosphere, from the oceans to the geysers, the dry valleys of Aantarctica and the most inhospitable deserts such as the Atacama.

Survival

Over their very long history bacterial colonies adapted to every possible environment and colonized every living organism. Their remarkable resilience may be the result of life principles tested over the eons during which microorganisms successfully met enough challenges to survive to the present.

While invisible to the naked eye their biomass influences life on earth at every level.

The invisible is enormous and omnipresent.

The eighteenth and nineteen centuries saw the discovery of microorganisms, the twentieth the beginning of their characterization. The twenty first century using new means inconceivable a few decades ago open endless possibilities to explore the complex relations between bacteria and all forms of life

We need a novel vision ofthe impact of these bacterial communities on the oceans, the soils and human health. Indeed, bacteria should be viewed as our allies and can offer concrete solutions to the major environmental challenges by establishing new agricultural practices that respect the quality of our nutrition and environment. We are on the brink of a true medical revolution that will only take place if it is based on a genuinely transdisciplinary approach and on massive investment commensurate with these health and environmental challenges.

We are living in a critical moment that will have a major impact on the future of humanity. We are emerging from a century of intensive agricultural production, based on monoculture, which aimed to meet the rapid increase in population. These efforts were justified. Malnutrition remains a major issue, and the quantity of food is an essential objective. But we are also facing a loss of understanding regarding the fundamentals of a healthy diet. Thus, we have to confront undernutrition in poor countries, as well as among poor populations in so-called “developed” countries. Simultaneously, we have to address the harmful effects of diets that harm health in economically wealthy countries—diets whose model we are transmitting to poorer nations.

Vibrant greenery thrives in a neatly organized soil profile, showcasing layered earthy textures, tendrils, and roots in a naturally lit, carefully arranged, and visually striking composition. To address these challenges, it is crucial not to forget that soils and their microbiomes offer us possibilities that remain largely untapped. In a way, the soil is the digestive systems of the earth! Agriculture begins with the soil, and its long-term productivity depends on soil bacteria. To benefit from this, we must use these bacterial communities as allies. The complexity, diversity, and symbiotic relationships within microbiomes are such that we are still far from understanding all the systems that govern their communities.

This blog intends to offer a broad and truly transdisciplinary view to these major challenges.

Each two weeks we will provide a short op/ed, to stimulate discussions.

We will also provide an updated library of many articles on this topic.